BAREILLY: For years, Sambhal had been a city known for what it had lost. Ancient temples, pilgrimage sites, wells — some dating back centuries — had apparently vanished under layers of alleged illegal construction and disrepair, their histories obscured by time and circumstance.

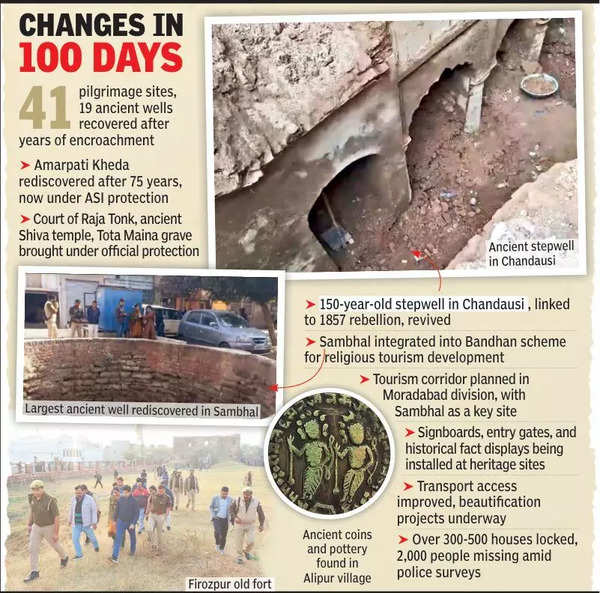

But in these past months, the district administration, working alongside the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), has rewritten that narrative, bringing 41 pilgrimage sites and 19 ancient wells back into public memory.

In the hundred days since a court-monitored ASI survey of the 16th century Mughal-era Sambhal’s Shahi Jama Masjid turned into a flashpoint of violence, the city has embarked on an unexpected transformation.

What was once a site of unrest — five dead, several police officers injured, fear thick in the air — has now become the stage for an ambitious “heritage revival”.

The authorities undertook a sweeping survey of the city’s “encroached and forgotten landmarks”, unearthing a past that had long been buried under decades of neglect.

Among the sites rediscovered is the court of Raja Tonk in Saraitareen’s Darbar locality, once a vibrant centre of power but now reclaimed from the shadows of modern buildings.

The Tota Maina grave, an ancient Shiva temple, and a 150-year-old stepwell in Chandausi, with its fabled underground tunnel linked to the 1857 rebellion, have also come under official protection.

Perhaps most striking is the “reappearance” of Amarpati Kheda, an ASI-protected site that had been considered lost for 75 years. It is said to house Dadhichi Ashram and 21 samadhis, including one believed to belong to Prithviraj Chauhan’s guru, Amarpati.

Sambhal’s story is not just one of historical recovery but of reinvention. The city, believed to be the place where Kalki — the 10th avatar of Lord Vishnu — will be born, is now a cornerstone of Uttar Pradesh’s religious tourism vision.

The Yogi Adityanath-led dispensation has folded its revival into the Bandhan scheme, planning to integrate these heritage sites into a broader tourism corridor spanning the Moradabad division.

“The administration has accelerated efforts to reclaim and restore lost sites,” said a senior official involved in the initiative. “Sambhal holds a special place because of its religious significance, and we are ensuring its history is not only preserved but also experienced.”

That experience is now being carefully curated. Manibhushan Tiwari, executive officer of the Sambhal Municipal Council, along with district magistrate Rajender Pensiya, has been leading visits to each recovered site, mapping out the logistics of their restoration.

“Each location will have a gate reflecting its identity, with historical facts displayed at the entrance,” Tiwari said. “We want visitors to walk into these places and feel the weight of their significance. The incarnations of Lord Kalki will also be highlighted, creating a deeper connection to our past.”

Transportation links are being improved, signboards installed, and the architectural character of the sites is being carefully revived to balance preservation with accessibility.

Yet, for all its progress, the city remains unsettled. In the narrow alleys, a quiet anxiety lingers. An 80-year-old resident, reluctant to share his name, spoke of a city that had not known such division in decades. “For 20 years, people lived in peace,” he said.

“Now, fear has crept back in. Many have left their homes. Loudspeakers have been removed from mosques. Even during Ramzan, the azaan is not being allowed in some places.”

The authorities say this fear is misplaced, a side effect of the crackdown following the Nov violence. A senior police official, speaking on condition of anonymity, painted a stark picture of the aftermath.

“Over 300 to 500 houses are locked, and at least 2,000 people are missing from the city,” he said. “Not all of them were involved in the violence, but they panicked when the police began door-to-door surveys. Many of these families have been living on land they don’t have papers for — land encroached after the 1978 riots. We have already freed the properties of three families from illegal possession. More will follow.”

Construction of a new police outpost opposite the Shahi Jama Masjid commenced on Dec 28. The outpost is likely to be named Satyavrat. In the meantime, 79 people have been arrested in connection with the Nov 24 clashes, and charges have been filed in six out of the 12 registered cases.